ReadWriteWeb : Netflix’ Daniel Jacobson: Letting APIs Change Everything

This article originally posted by Scott Fulton on ReadWriteWeb on February 3, 2012 as Part II in a series. Part I can be found here.

What we today call the “mobile app” could, in a very short period of time, become known as the portable app, or just the “app.” It tends to use such a simple and straightforward model of interaction that people are starting to prefer using their smartphones for certain tasks, even when their PCs are right in front of them. By this time next year, portable apps originally designed for use on smartphones and tablets may be running on laptops.

The extent to which this changes everything is a topic that no one, not even ReadWriteWeb, has fully fathomed. The Web as we have come to know it will be affected significantly. What users have come to know as Web sites will be willingly and eagerly substituted with Web apps. In Part 2 of our interview with the co-author of APIs: A Strategy Guide, Netflix lead API engineer Daniel Jacobson tells us the one huge difference between an app and a site involves the extent to which they rely on an API. It is part of every app’s DNA.

The First, Painful Steps Toward Multi-Platform

In 2002, as you learned from part 1 of our RWW interview last week, when Jacobson was with NPR, he helped make a critical decision about its information infrastructure, the implications of which his team had not foreseen: “Literally the first thing that we did,” he tells RWW, “is, we built the API and we put the Web site on top of it. So the Web site runs off the API. It’s a little bit of a different interaction model; it doesn’t have to go through the authentication and whatever else, in the same way that external apps do.”

That API later gave NPR the freedom to build apps that run outside the browser, and that use that same API in different ways. So when mobile apps were invented, NPR was among the first publishers to be ready for them. When Netflix saw it needed an architecture that enabled it to reach all its users without it being dependent upon the usage model for any one device, including the Web browser, it hired Jacobson to build it.

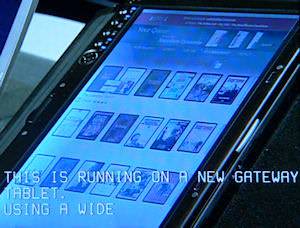

A 2005 Netflix demo at a Microsoft convention featured one of that company’s program managers at the time, Darryn Dieken, showing then-President Jim Allchin the prospects of using one underlying technology as the foundation for developing a unified product line across different devices. The technology at the time was code-named “Avalon,” and evolved into what we now call Silverlight.

After showing how a Netflix product selector ran outside the browser but through the Web, in a way people had never seen before at that time, Dieken showed essentially the same selector running inside Windows Vista on a tablet PC. From there, he proceeded to show where else folks would eventually find Netflix.

The demo took the audience inside Windows Media Center, which had just been released for Windows XP and was being vastly updated for Vista. The Media Center plug-in used many of the same presentation techniques and concepts as the stand-alone version, demonstrating the benefits of code reuse.

But when the demo turned its attention to Netflix on a Windows Mobile phone, it became painfully obvious that the benefits of client-side code reuse could only go so far. Yes, there was communication taking place between all these different clients and the server. But the way these interactions were happening were based on leveraging Web site-oriented, forms-based submissions that at one level could be described as an API, but failed to be uniform – one API for many platforms.

The goal of any modern API, Dan Jacobson emphasizes, is “to treat any presentation layer the same. So if you have multiple Web sites, like NPR does (they have NPR Music as well as NPR.org), both of those sites run off of the same interaction model through the API. They’re just presentation layers, the same way as mobile app or Google TV or [NPR] Infinite Radio. Users are going to consume new material in any way that they want to, wherever, whenever; and your goal as publisher is to make sure that you have a presentation layer that serves them wherever that is. And in doing so, the easiest way, the most effective way to date is to leverage APIs, and invest a little bit on having the right talent surrounding it.”

“Publish Everywhere” Doesn’t Have to Be Homogenous

Because presentation layers are so different from one another, he goes on, a business can and should nurture teams of developers with the exclusive skillsets that each of those layers needs – for example, Objective-C developers for iPhone apps. There’s no reason why certain teams can’t specialize. Having a single API that addresses each layer in a standard way, he says, provides all your teams with the flexibility they require to take advantage of the platforms on which they’re focused.

This allowance for specialization tends to work itself away from the “one Web” way of thinking, the belief that everything will inevitably merge into HTML5. In professing that API design should not be centered around any one single mode of presentation, lest it eventually become obsolete (among other reasons), Jacobson advises that API designers focus on finding ways to symbolize and encode business interactions, the things that businesses do, not the things that Web sites do. Your goal is not to make the browser more efficient or the user experience more immersive. Leave that to the UX designers. As the API engineer, your goal is to enable business.

“That kind of thinking is fundamentally different than, ‘How do I want to structure my content? Do I need to think about what resources can be broken up in which ways and made available in different ways?’” says Jacobson. “For NPR, for example, there are stories, there are assets, different kinds of things in that system. For Netflix, there are users, catalog items. How do you want to structure that material, both in terms of the resource level as well as items underneath it? What are the rights management concerns that go into this, legal constraints internally about what can be published? For Netflix, what can I show users in Latin America that I can’t show to people in Canada? For NPR, it’s, I’m publishing AP photos; whom can’t I present that to, and whom can I? Those kinds of things are really business-oriented decisions that you can’t just flip a switch and say, ‘Make it happen.’ You need to be very thoughtful about what you’re exposing and to whom, and how you’re going to do it so you can get the maximum effectiveness out of it.”

It is this concept which may outmode, or render obsolete, the traditional notion of the Web site, the notion that something that’s created once and published everywhere (COPE) must always be the same thing. Done properly, Jacobson says, it can and should be integrated with the uniqueness of each device.

“When Web APIs started out, they tended to be more about publishing on all kinds of different platforms. Now I think it’s very much about aggregation, and merging others’ API experiences,” says the Netflix engineer. “One of the interesting things with Netflix, for example: We have branded apps on a wide range of platforms, and if you look at something like AppleTV or Roku or Xbox, or any of these other devices, we’re not the only ones there. There is an aggregation of services where Netflix creates an experience on that platform. We actually integrate with their systems, we’re creating an experience on that site, and then people can access our experience in the way they expect it to be presented.”