Forbes : Why APIs Now Mean Business Transformation, Not Just Technology Infrastructure

This article was originally written by Dan Woods and published on Forbes on March 23, 2016

Thirty-six years ago, my first consulting project was fixing an IBM 360 assembler language program that had broken because the behavior of one of the machine instructions had change subtly. At that time, you could consider the definition of the IBM 360 assembler language an API to the hardware.

In the years that passed, the idea of the API has changed. We’ve moved from LPA libs, to JCL, to Microsoft DLLs, Java packages and Python libraries. The strict definition of the term “application programming interface” suggests that the API is a tool of abstraction and simplification. The application developer doesn’t want to want to have to worry about the details of how to send a text message from a mobile app or how to run an analytics routine in R or how to display a graphic using the D3 libraries.

Where is your API journey taking you?

Because of this legacy, APIs are most often seen as something deeply technical, and this impression lingers to this day. But as Google and Yahoo rose out of the wreckage of the dot com bust, as Facebook and Twitter were born, the technological essence of APIs is giving way to a more business-focused emphasis on enabling unfettered innovation.

The APIs of Google, Yahoo, Facebook, and Twitter in the mid and late 2000s were unusual in that they were public. These APIs did have a technological purpose. They abstracted the basic capabilities of publishers so that they became useful for developers. But the point and the value was unrestricted innovation. SAP had APIs decades before called BAPIs that allowed their massive ERP system to be controlled. The trick that the Internet darlings performed was to figure out that by making APIs public, by allowing self-service, a seething tribe of creative developers could put those APIs to use creating new ways to put the core services to work. John Musser, the founder of Programmable Web, was the prophet of this era.

For example, Google Maps was one of the first public APIs to be created, inspired in part because developers figured out how to use Google’s capabilities on their own in an unauthorized manner. Google quickly realized that this was a great idea, published APIs, and a flood of innovation and use of Google Maps followed. Yahoo, Twitter, Facebook, and Amazon followed the same pattern for many of their services.

So in this era, John Musser created a catalog of public APIs and Chet Kapoor of Apigee and other companies like Mashery, now part of Tibco, and others created products to allow everyone to get in the game of creating public APIs. Working with the CTO of Apigee, Greg Brail, and Daniel Jacobson, VP of Edge Engineering at Netflix, I co-authored APIs: A Strategy Guide (O’Reilly), a book about API strategy. (Disclosure: I have done work as an analyst and content marketer for Apigee, Intel, Tibco, Microsoft, and other companies who sell API technology. For a full list of my clients visit EvolvedMedia.com/clients.)

Forbes Daily: Join over 1 million Forbes Daily subscribers and get our best stories, exclusive reporting and essential analysis of the day’s news in your inbox every weekday.Sign Up

By signing up, you agree to receive this newsletter, other updates about Forbes and its affiliates’ offerings, our Terms of Service (including resolving disputes on an individual basis via arbitration), and you acknowledge our Privacy Statement. Forbes is protected by reCAPTCHA, and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

The point of that book was to explain the notion of APIs from top to bottom, but also to explain how APIs had become far more than just technology infrastructure.

How APIs Have Become the Building Blocks of Business Transformation

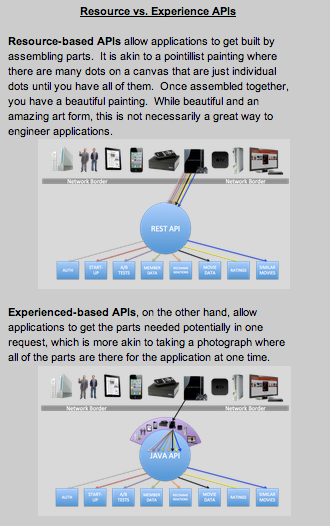

Daniel Jacobson’s evolution of APIs at Netflix shows how APIs can become building blocks for business transformation. Jacobson is in charge of creating the API infrastructure to support product development. Netflix, like many other companies, had a set of “resource-based” APIs that exposed the core capabilities of the key operational systems. Using these APIs, you could get to the catalog information on Netflix and invoke services to play movies.

Jacobson and his team determined that the code they were writing to create Netflix clients for various families of devices such as iPhones, iPads, Android tablets, DVD players, and so on was far more complex than it needed to be. The problem was that resource-based APIs were built to expose the capabilities of key systems in a general way. That mean that the client code had to do all sorts of stuff like transform and combine data, connect information from a multitude of sources, and create data structures and navigation that matched the needs of the device.

Jacobson’s team realized that a new layer of APIs was needed, which they called experience-based APIs (see “How A Netflix Tech Innovation Can Unleash Creativity in Your Business”). This layer of APIs was created not by the teams in charge of the key operational systems, which created the general purpose resource-based APIs. Rather, the developers in charge of creating clients for all the devices used to access Netflix defined just the APIs needed for each family of devices. The experience-based APIs moved all the code for transforming and formatting data and adapting the resource-based APIs to the needs of the device into the experience-based API. Jacobson’s team found that this process could be accelerated by allowing the experience-based APIs to be created using a scripting language. Jacobson and his team packaged this idea as the Nicobar open source project.

APIs as a Unit of Digital Business Design

FinTech and other industries have taken the general pattern of experience-based APIs and adapted it to different circumstances. Consider these examples:

- Tradier has created a Brokerage-as-a-Service offering that is a combination of resource- and experience-based APIs. Tradier customers are able to embed the ability to research and trade stocks within their existing applications.

- Orchard Platforms has created a platform powered by APIs that normalizes access to lending marketplaces. Using this platform, large financial institutions can make loans on platforms like Prosper and Lending Club using automated underwriting.

- Xignite has created a set of APIs that normalizes access to a vast amount of financial data. Some of these APIs are resource-based, providing general access, and some are experience-based, focused on meeting a specific need.

- Bechtel has introduced huge amounts of efficiencies by creating a platform as well as resource- and experience-based APIs to enable the creation of mobile apps. On job sites around the world, instant access to information has dramatically reduced delays because workers don’t have to go to sheds to access computers.

The point to remember is that all of these APIs are both technical artifacts and units of digital business design. As technology infrastructure, both resource-based and experience-based APIs need to be supported by generic API gateway capabilities such as:

- Proxy support

- Authentication/Authorization

- SSL/TLS termination

- Encryption

- Logging

- Load balancing

- Routing

- Throttling

- Lightweight orchestration

But there is another business-focused process going on here as well: the process of developing the unit of business design. In other words, resource-based and especially experience-based APIs are not designed simply as technology artifacts, but as ways to enable a business purpose. The people involved in designing the desired digital business experience must be involved.

Enterprise-grade API management – the kind that can power digital transformation and drive a business – goes beyond an API gateway and supports an ecosystem of digital collaboration. Many types of software follow this path. The software starts out supporting specific, targeted functionality but ends up adding features because people want to collaborate and need supporting capabilities as the original function becomes more important.

When you are using APIs as a unit of digital business design, you need capabilities such as:

- Analytics about developers, operational performance, app performance, and business metrics

- A customized developer portal

- API monetization

- Multi-tenancy and support for high scale

- Global policy enforcement

- SDKs for all popular development environments to simplify the process of developing an API

- Support for adding application code and data to the API infrastructure to enable distribution of code and data

- A powerful transformation engine to speed the task of adapting resource-based APIs to experience-based APIs

It is perfectly possible to use APIs as a unit of business design without an enterprise-grade API management platform. The challenge then becomes creating enterprise capabilities when you need them and supporting them over time.

The API marketplace is evolving rapidly. Amazon recently released an API gateway product. Microsoft has one as well, and there are various types of open source toolkits and such. The functionality of many of these vendors’ products supports the notion that APIs are simply technology infrastructure.

But vendors like Apigee would argue that to really use APIs as a unit of digital business design, to accelerate the creation of business value that comes from apps that can be developed faster and that cost less to maintain because of practices like experience-based design, you need much more than an API gateway.

“APIs have gone well beyond just bits of technology – they are essentially the foundation for digital transformation,” said Apigee’s Kapoor. “We believe that businesses will need to use APIs and API management to support digital business initiatives or risk becoming increasingly irrelevant.”

The challenge in my view is the legacy that APIs have as a unit of technology infrastructure. The people who are buying solutions are often thinking small about APIs rather than thinking big. The challenge for anyone using APIs is to stop thinking of them only as technology and to start thinking about the results you want to achieve and how APIs can play a role in getting there faster.

Dan Woods is on a mission to help people find the technology they need to succeed. Users of technology should visit CITO Research, a publication where early adopters find technology that matters. Vendors should visit Evolved Media for advice about how to find the right buyers. See list of Dan’s clients on this page.