The Next Web : The future of API design: The orchestration layer

This article was originally published to The Next Web on December 17, 2013

The digital world is expanding at an amazing rate, giving us access to applications and content on myriad connected devices in your homes, offices, cars, pockets and on even on your body. The glue that allows all of this to happen, that connect the companies who provide these services to the devices that you use, is the API.

Because APIs have such a huge responsibility for so many people and companies, it is natural that API design is often one of the industry’s liveliest discussions, touching on a range of topics including resource modeling, payload format, how to version the system, and security.

While these are likely important areas to explore when designing virtually any API, the reality is that a much larger decision needs to be made first. That decision is based on a fundamental question: who are the primary audiences for this API and how can we optimize for those audiences?

This seems like an innocuous enough question, but don’t underestimate its importance or complexity in the growing world of APIs.

Years ago, this question was much simpler

At that time, many emerging APIs were being built as open or public APIs, targeting a large set of unknown developers (LSUDs) external to the providing company.

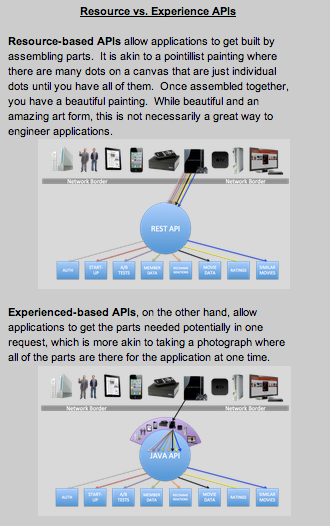

Because of the (hopefully) vast numbers of external developers using the API representing different use cases, the most sensible way to design the API for this audience is to have the providing API team design it in a very clean, concise, and resource-oriented way that closely represents the data model and/or features of its source(s).

In a previous post, I referred to these as OSFA APIs (or one-size-fits-all APIs). Allowing for such granularity in the modeling means that any developer who wishes to use the API can mix and match the elements in whatever way they choose to satisfy their application without further API team involvement.

The resource-model approach to designing an API can be very powerful, especially for this type of audience. The problem with this approach, however, is that the way that many companies use APIs today is different than described above. While many are still supporting the use cases of LSUDs, more are using their APIs to support a growing mobile or device strategy.

For some of these implementations, the engagement with the developers is different. The audience is a small set of known developers (SSKDs). They may be engineers down the hall from the API team, a contracted company hired to develop an iPhone app, or an engineering team in a partnering company. In all of these cases, however, the API team knows who these people are (at least in the abstract sense).

More importantly, however, the API team and the providing company care about the success of these implementations in a different way than they might care about the applications developed by the LSUDs. In fact, the success of the SSKDs may very well be paramount to the success of the business as a whole, a model that is becoming increasingly more pervasive.

Because of this change in audience and the deep interest in their success, there is great opportunity to change the API design.

For the SSKDs, having granular resource-based APIs that closely represent the data model works, but it just isn’t as optimal as it could be. This is especially the case when you consider the growing number of device types in the world and the fact that more and more companies’ business strategies are dependent on providing value to customers on such devices.

So, all it takes is a couple of devices with diverging needs and/or capabilities, each of great import to the company, for the resource-based API to start to show some warts. Making the API better, more optimized, for each of these target applications is the next logical, and most critical, step.

Enter the Orchestration Layer

An API Orchestration Layer (OL) is an abstraction layer that takes generically-modeled data elements and/or features and prepares them in a more specific way for a targeted developer or application

To address this opportunity, more companies are employing orchestration layers into their API infrastructure. While there are many ways in which to implement this architectural construct, the concept remains the same across all of them.

Below, I will describe a few of the more common patterns that I have seen (and/or been involved in implementing). But first, here are a few key principles that need to be considered when building an OL:

1. Most APIs are designed by the API provider with the goal of maintaining data model purity. When building an OL, be prepared to sometimes abandon purity in favor of optimizations and/or performance.

2. Many APIs are designed by API teams to make it easier for the API team to support. When building an OL, be prepared to potentially add complexity for the API team (or other teams, depending on the way it is implemented).

While this sounds undesirable, the goal here is to dramatically improve efficiency and/or simplicity for other people at some mild cost to the API team. Also keep in mind that such costs can potentially be programmed away over time.

3. It is important to understand the breadth of the audiences for the API.Depending on those constituents, you may only need the OL. In other cases, you may need the OSFA foundation in addition to the OL.

Here are a few examples of how some OLs have been approached:

Device-specific wrappers

This is the most common pattern that I have seen because most companies that are experiencing the distress referenced above already have APIs that they still use, continue to support, and invest in. The result is to continue to offer the granular resources as they always have, but to offer a wrapper tier on top of them – with new endpoints that are tailored to specific developers, devices or device clusters.

In this model, the API team will work more closely with, for example, the iPhone team to write a custom wrapper that handles specific requests and deliver specific payloads that are optimized for the iPhone app. In this model, most often the team to build the endpoints and the wrappers is the API team although that doesn’t have to be the case.

Query-based APIs

In this model, the API team is putting the power in the hands of the requesting developer, although that power is limited. The goal here is to create a more flexible way in which the requester can make requests and tailor payloads without putting additional ongoing burden on the API team, as could be the case with the Device-Specific Wrappers.

This is achieved by breaking down the resource-based APIs and allowing them to be queried against like a database through flexible parameters and payloads that can contract, expand and possibly morph based on what is needed. The benefit here is that once the query language is set, the API team does not need to keep writing wrappers as new implementations are needed for different devices.

The detriment, however, is that the query-based API is still a set of rules to which the developer needs to adhere, although these rules are much more flexible than the resource-based API model.

Experienced-based APIs

This is the model that Netflix has implemented, which in some ways is a blend of the two above. In this model, we basically have device-specific wrappers but they are designed, implemented and owned by the device teams.

A key concept here is that we have put the API team in the position of gathering the data in a generic, reusable way while putting the device teams in the position of owning the data formatting and delivery. After all, the formatting needs evolve in concert with the UI changes so putting that effort in the hands of those closest to the changes eliminates additional steps.

(For more details on how this system operates, see the links at the bottom of the post.)

As I noted, the range of implementations is potentially much more diverse than these three, although these are some of the most consistent and interesting patterns that I have seen. Regardless of how this is achieved, however, the key is for the API team to stop supporting the API as a service that is designed independent of those SSKDs who consume it.

Rather, the API team needs to view the SSKDs as partners in the design with an interest in making the products as great as possible so the end-users can get the best experience possible. The API team has the opportunity to build services that help developers to be better at developing by focusing on optimizing for the developers’ needs rather than how to optimize the time spent supporting the API.

Given the opportunity ahead with the potential number and diversity of connected devices, the effort to provide such optimizations is a small price to pay for the massive upside.